My Journey In Psychology

Through my journey in psychology and mental health, I realized what most people miss regarding mental health, despite it being so obvious!

I went into psychology hoping to help others and understand myself more deeply. I especially wanted to know why us people knowingly choose to imperil ourselves, future generations and our entire planet. What I saw in academia helped me see more how misguided we are in such pursuits. This helped me find the path that would change my life forever. Turns out, it was always right in front of me.

My father was a psychologist, so you could say I was born into this field. He also took me backpacking from the time my little legs could carry a pack. That likely changed my life more than anyone would realize.

I was a pretty awkward kid, without many friends in elementary school. During middle school, I was diagnosed with ADHD. I was rowdy, for sure, and lost stuff all the time. Plus my attention was very specific and hard to capture without getting my interest. I also think my time in nature changed how I viewed the world, and what I was being taught.

For one thing, I had zero interest in the history of our country, or “civilization” in general. These people just seemed to wipe out the native populations, who were far better at caring for the land than we were. Needless to say, I had little time or attention for what I was supposed to be learning, even though I was smart enough to. So my grades didn’t match my abilities. In graduate school, I’d learn this is called the “discrepancy” diagnostic method for ADHD.

I had then, and still have, a very strong capacity for focused attention when it aligns with me. But I wasn’t doing what I needed to, according to the school, and by extension, society.

But my diagnosis gave me 2 things; Drugs (Ritalin) and access to people who gave me their focused attention, aka. the “resource room” teachers. This is what I most needed, as I believe any youth does. And it helped me immensely. This realization would later spur me to do a research experiment on all this.

Between the drugs, teachers, and my newfound outlet for my energy in the depths of winter, my grades turned around through high school. I got accepted by several colleges and ended up going to West Virginia University.

I became very concerned about global warming around the beginning of college in the mid-90s. It wasn’t yet a common concern, especially for teenagers. But I was afraid the snow would disappear during my lifetime. I mean, the east coast hardly had any snow as it was!

I looked into alternative energy briefly and thought about going into engineering. Math had always been my strongest subject.

But I found out that we had alternatives to fossil fuels already. This was when it sunk it that we were choosing to use to use unsustainable energies for some reason. It wasn’t because we couldn’t, it was quite literally the way we chose to do it. Why in the world were we doing that!?

During my sophomore year, I went to a job fair and found a rafting company looking for river guides. So I did what any broke college kid without a car would do, hitchhiked across West Virginia, lived on the property in my tent for the summer, and learned how to guide rafts down a Class V river.

This would change my life in several ways, not the least of which was being part of a community—one that was connected to the earth, especially the river. I felt like I belonged, for the first time in my life.

I also learned a skill that would get me out on all kinds of adventures in the future. And I found a love and understanding for rivers that would shape how I saw nearly everything.

I worked on different rivers part-time and seasonally through the rest of my time in college.

Back in school, I decided to major in psychology. I needed more insight into what the hell us people were thinking, especially after having such a life altering-experience.

I learned about a bunch of theories of personality. There was Freud and his obsession with sex, Skinner and behaviorism, Pavlov and his dogs, and more. Each of them made some sense in one way or another. But all of them seemed like they were missing the mark to me.

Maslow’s hierarchy, where “peak experiences” lead to “self-actualization,” got my attention. I had already had one of the former (that’s another post entirely). I was hoping there would be more focus on such things in psychology.

There wasn’t much of a road map to these elusive experiences, though, or how they translated into anything more than a momentary glimpse. Most other views considered them psychotic breaks of mania, delusions, and hallucinations and would aim to tamp them down with drugs.

Through years of searching, nothing I came across really captured the essence of human consciousness well. At least not the way I saw things. And nothing ever came close to addressing why we make the crazy, self-destructive decisions us people make.

So I tried to forge my own path in research. In the majority of my psychology classes, teachers would speak of how psychology was indeed a science and that research was the key to understanding human consciousness—specifically quantitative (numbers-based) research. I had no idea how misguided this thinking would become to me later. But it was something I could sink my teeth into. And I went all-in on it.

After graduation, I stayed in contact with a research-intensive professor to conduct an experiment. I also found a job at a residential school for teens with learning disabilities.

The goal for the experiment was to put both of our names on a published research paper in a peer-reviewed journal. Between that and my work experience, I could get into a doctoral program and study human consciousness as a career. My professor helped me put together a study, and I was off!

I credited a lot of my success in school to the special teachers and others I had access to after being diagnosed with ADHD. They knew and cared for me, but they weren’t tied to me or my life personally. They could give a different perspective than anyone else involved in my daily life. They had more experience than my peers, and I listened to them differently than my parents.

So I figured that people like shrinks, clergy, or others who had some experience with the people yet were personally detached were more able to offer people sound advice. So I created a survey about this, threw it in with a larger study that my professor did with incoming first-year students, got the results, and Boom! It turns out I was right, well beyond the statistical probability of random variance. In other words, I found something!

But the research was only one relatively small part of the process. I then had to write about it. And oh my, was it tedious!

First, I had to check all of these other related studies and reference them. I could only get them in the school library at the time. I dreaded reading and researching these things. Even though I was interested in what they said, it was the driest and most boring way of writing imaginable. And there were entire libraries filled with this stuff! But here I was, trying to contribute to it all, thinking it would make a big difference.

Writing it was even worse. I had to break it up into these weird sections. I had to detail the math we used, describing the statistical measures. This was as boring as it sounds, but there was something else I didn’t get back then.

By using statistical norms, we were comparing ourselves to each other, all immersed in the same culture. We were measuring our fit to it, to the way things stand. In other words, we were trying to help people to be “normal”, and using those who fit into society as it stands as the norm. Why the hell were we doing that!?

I trudged through this paper, edit after edit. After several years, I was getting nowhere. I was miserable. I still dreamed of the research and what else I could study. The questions I could ask kept coming. But I eventually realized the writing, not the investigation, was the actual job.

My job at the residential school wasn’t getting me anywhere either. I liked the kids and my co-workers, but we weren’t helping anyone there. We were just dealing with kids who were going through things. Kids who couldn’t be what other people wanted them to be; normal. We were putting it all on them, and they acted out about it. That certainly wasn’t enough to satisfy me in my search for… what even? I was lost.

After four years like this, I decided to move on. So I picked up and went to Oregon.

I moved to Oregon because of the rain. During my time as a river guide, I got into kayaking as well. Oregon is great for white water, with water falling from the sky for so much of the year. Within a few months, I met a bunch of kayakers as crazy as me and found work at a wilderness therapy program, thanks to my background.

This program was for teens who were having difficulties in one way or another. Many of them were doing the same things I did growing up; they just got caught more often.

The program started with a 3-week outdoor adventure. They learned a bunch of skills leading up to a three-day solo period. About half of the kids were ready to leave the program after that portion. If not, they went through an additional 4-week program. Few would stay on and go to the school portion of the program, where they would stay from 3 months to a year. That’s where I was.

I already had a handful of jobs in mental health programs through the years. In just about all of them, there was a tangible feeling that the kids were just going through the motions. In retrospect, the programs were pretty much designed for that.

We just pushed the kids to do what we wanted, what we thought was best for them. They had two choices; buy-in or deal with the consequences.

There was little regard for what they were going through. We should have been helping them accept, understand, and process who they were. The best thing for them was to love themselves and their lives. Instead, we wanted them to be something they just weren’t.

We would try one reward system, contract, or strategy after another to get them to act “better.” If they got too worked up about it all, they’d end up in restraints. It was now clear that this had little to do with health, mental or otherwise.

In the wilderness program, everything was different. These kids were discovering themselves. The feeling of community was vibrant, and the kids were invested in it and each other. They would readily reflect on their emotions and check in with peers and staff. We talked about real stuff, big picture, and personal.

Every single person involved in the program changed. They told me the job would challenge me in several ways when I first got there. And it did. During my first week working there, I nearly drove off mid (week-long) shift. But I stayed, faced things within myself, and grew. And I saw what I thought to be impossible changes in these kids.

It was apparent to me that the environment opened the door to everything else. This was the first time I realized that everyone should do intentional self-work in wild nature.

All of this wasn’t without issue, though. The hours were tough, and so was the lifestyle. I spent a week at a time on, with less than 10 hours of break time. I ate with the kids and slept in the same lean-to.

To continue doing this, I would have had to live in the middle of nowhere, which still isn’t much of a desire of mine. This was true of any role in the program. And the pay wasn’t enough to keep up with bills. I couldn’t see myself doing this type of work for life. Plus, the field of wilderness therapy was also in a difficult spot.

When they went home after the program, they typically returned to the same situation as when they left. And we had to break contact with them. So all of the support, the community, and the environment they had was instantly gone.

They could have had the most meaningful experience of their lives, and I have little doubt some kids did. But they went back to a place where no one understood what they went through, and they had to deal with the same stuff from others as when they went in. They probably felt more isolated than before.

At the end of the day, the effectiveness of these programs is based on relapse rates (to their previous behavior, not necessarily drugs). What would you do if the most meaningful thing you have experienced suddenly disappeared and no one you knew could relate to anything close to it?

This was a big knock against wilderness therapy in general. It doesn’t translate to success in our human-made world well. It was apparent to me why. The problem wasn’t with the program. It was with the environments the kids went back into.

In no small part due to this, the program wasn’t supported by insurance. It downsized, and I lost my job at the end of my first year. It would shut down a few years later.

After my time there ended, I couldn’t see a path in psychology anymore. Right when I began to find answers to the question that was guiding me, it came with a whole new set of issues. So I put my journey in psychology on pause, went to Japan, and taught English for what ended up being the next four years.

While in Japan, I realized, among myriad other things, that I didn’t want to be a teacher. I applied to graduate school back in the States, and I got into a school psychology program in Portland. It turns out a school originally psychologist diagnosed my ADHD all those years ago! So I moved back to Portland to settle into a career, or so I thought.

Now the role of a school psychologist is to identify students with special needs, find ways to help those kids succeed in the areas they are struggling and get them help, often in the form of an individualized education plan (IEP). There’s a lot more to the role than this, but that’s the trick that only the school psych can do.

The kids were almost always struggling in math, science, or English or acting out in the classroom. Those things usually went hand in hand. Whatever other skills, talents, or passions the kids had, the school required those specific competencies from them. School funding was based on the students’ level of aptitude in these areas, after all.

I was as interested in shifting school culture as much as any other aspect of the job. I thought schools could be far more supportive and community-centric and that students could be empowered to drive all of this given the right culture. My program supervisor enlightened me that culture was far more of an administrative issue. And there was another force pushing me in a different direction.

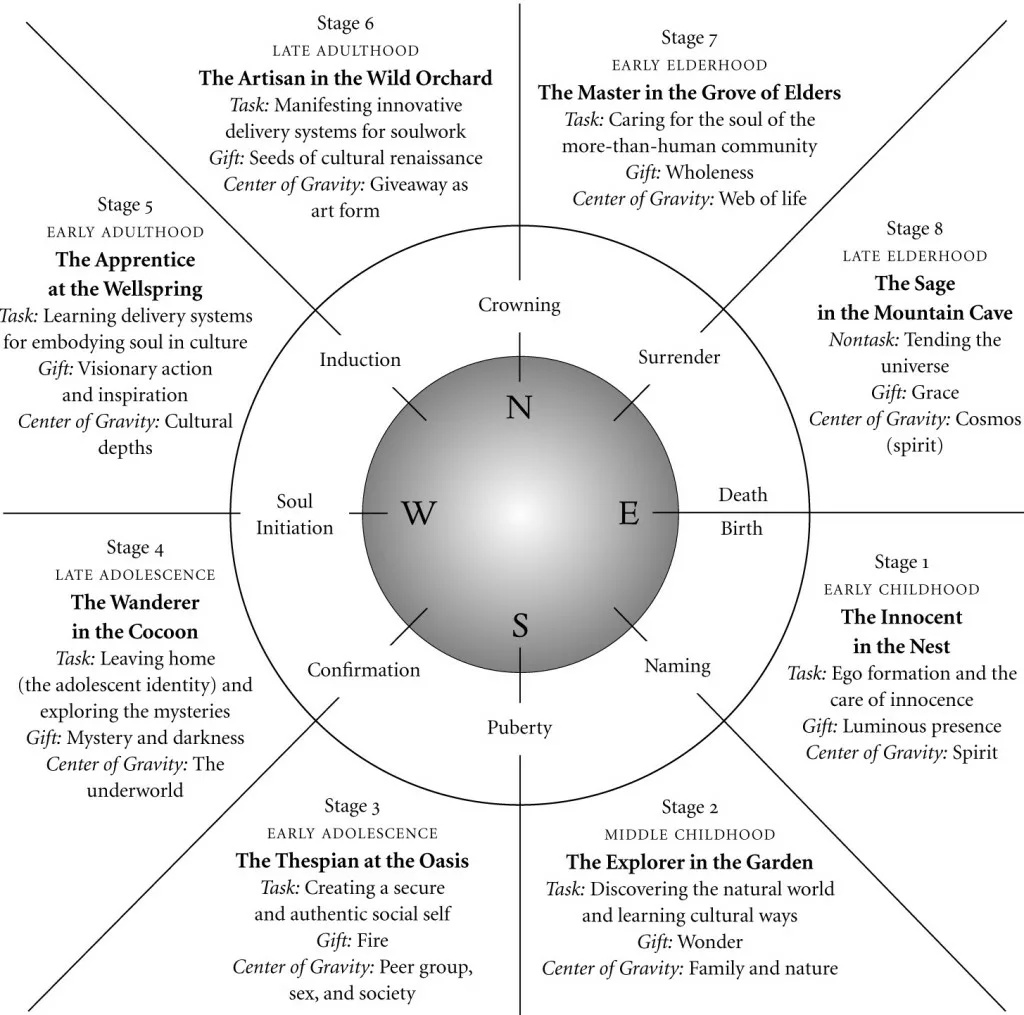

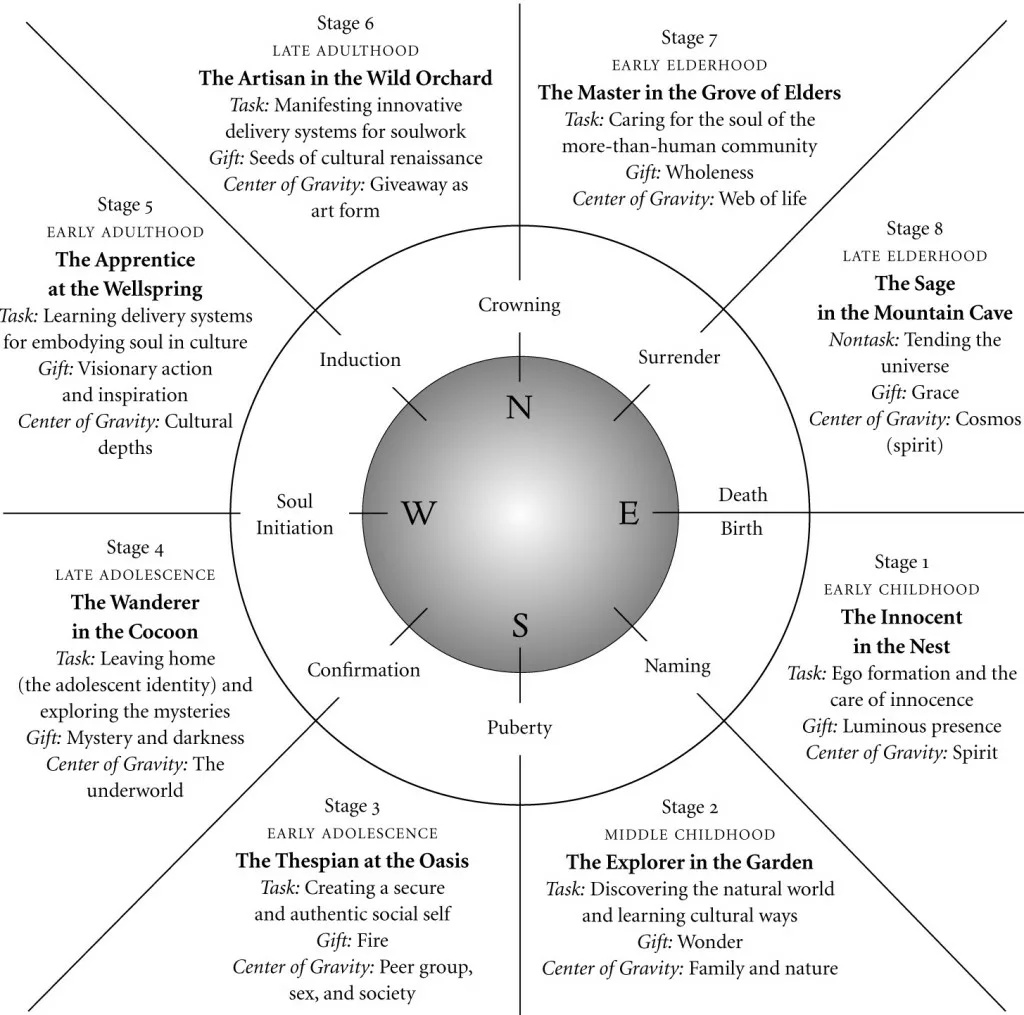

I also took a lifespan development class during my first semester in the program. The professor offered a brief introduction to various models of human development. One was written by Bill Plotkin and viewed from an Ecopsychology perspective.

It spoke to the questions I had been holding my entire life, unanswered by other theories in psychology. Mainly why we were doing the things we were doing. And he supported moments of vision! Plus, the developmental stages made sense. They were applicable to everyone, regardless of culture. It was exactly what I had been seeking for so long I had stopped looking altogether.

The problem was that nearly everything about this perspective was at odds with what I was learning in school psychology. But I started diving into this framework more and more.

Meanwhile, like the rest of the mental health industry, the school psychologist was trying to be entirely data-driven. Their data was all about their performance in math, science, and English. And of course, it used normative measures as the standard. It gave little merit to the vast majority of the capabilities that comes with being human. Things like arts, physical abilities, EQ (one of my strongest capacities), social skills, and more.

I began seeing that we weren’t helping students learn how to be better people or even offering them mental health help. We were just making them jump through our hoops and using diagnosis to put it on them when they couldn’t. It may have helped them in school, but I was seriously questioning the point of even that now.

It all was conditioning them to contribute to things as they were. It wasn’t really to help the kids become comfortable with themselves, warts and all. Again, if it didn’t help with math, science, or English, it wasn’t worth the time or energy.

Outside of this, the professors and the entire department only cared about the work I did, not what was going on with my life. I was going through one of the most challenging times of my life outside of school, and it fell on deaf ears.

They were preaching mental health but not practicing or regarding it highly. The message was clear; my mental health was a secondary concern to my work.

I saw this as incredibly hypocritical. I even let one of my teachers know about it. The split was inevitable.

After four semesters, my journey in school psychology, and ultimately traditional mental health, ended. Fortunately, that same tiny graduate program had the perfect alternative. I could switch programs and, within a year, got my Master’s in Cultural and Psychological Studies with a certificate in Ecopsychology from the Lewis & Clark Graduate School of Education and Counseling. I call it a Master’s in Ecopsychology cause I’m into the whole brevity thing (usually).

Along with my newfound awareness and the model of human development, I also discovered the Hero’s Journey, a template for the journey through deep-seated change. All in all, though, graduate school was a rocky, expensive road.

Graduation itself turned out to be the beginning of the real journey. I then went on a year-long immersion experience at Animas Valley Institute guided by Bill Plotkin himself. I joined gatherings held by the Wilderness Guides Council. Those things combined cost about 3% of what graduate school did, and I got much more out of them.

I began working as a guide again for my trips and working for others. I found wilderness programs that work and several that don’t. Most importantly, I was answering the questions that have guided my quest in ever more expansive ways.

I started Evolve Wild because, as far as I know, there’s nothing quite like it. I believe it’s exactly what people need at this time: The first step on your personal journey to deep-seated change.

The world us people have created is simply unsustainable. It’s not because we can’t be sustainable. It’s because the values we operate on, the ones our human-created world imposes on us, are immature. They keep us acting in self-centered ways, not reflective of the responsibility that comes with having the power us humans do. It’s built into the way each of us sees and does everything, especially when we’re immersed in this world. And there aren’t many ways out of all that.

Evolve Wild does get you out and in touch with an infinitely larger perspective. It helps you clearly see yourself, your true, wild, authentic self.

The aim is to help you to fall in love with the world in which you, and all of us, live: the one that still miraculously supports you, me, and our crazy human-centered society. And to fall in love with your life again. To find, get to know, and live into, that version of yourself. To love pieces of yourself that you’re conflicted with, even actively suppressing.

This alone will help you be more true, authentic, and loving in everything you do. It moves you along in your development, both in yourself and affecting the larger culture. You become the change simply by loving who you are and honoring what you bring to the table.

Doing this well can be a long, difficult process. When things go right, you will return to a world and a life that no longer aligns with you. You’ll have to make changes to live into what you find. You’ll have to trust yourself deeply as you honor your values and feelings.

When you do, things open up for you in more ways than you can imagine. You start to evolve as you live into your wild nature.

Leave a comment below!

I’m curious about other people’s experiences as well. Have you been through therapy or mental health? What did you get from it, or felt it was lacking?

I’d love to hear from you if you have been through a wilderness experience. I’d also love to hear from other mental health professionals.

Feel free to join the community and find more people doing this!

Through my journey in psychology and mental health, I realized what most people miss regarding mental health, despite it being so obvious!

The Soul-Centric Developmental Wheel offers a model of the development of our deeper, complex human nature.

Whether we continue to act as self-serving individuals (ego) or as unique beings in an interconnected world (soul) will determine our future.

Ecopsychology explores the our relationship with both the natural world and the human one. It deeply affects our health, and the planet’s.

Do you ever wonder how the world got this way? Do you think it’s human nature, or is it the culture we’ve created? And how can we change it?

We all have a relationship with nature, whether you realize it or not. Here are 9 practical ways to deepen that relationship.

Through my journey in psychology and mental health, I realized what most people miss regarding mental health, despite it being so obvious!

The Soul-Centric Developmental Wheel offers a model of the development of our deeper, complex human nature.

We are offering a limited number of experiences in 2022. See what’s still available!